Olive oil production begins with harvesting the olives. Traditionally, olives were hand-picked. Currently, harvesting is performed by a variety of types of shakers that transmit vibrations to the tree branches, causing the olives to drop into nets that have previously been placed under the tree canopy. Increasing ripeness generally increases yield in terms of release of olives from the tree branches. However, over-mature olives do not possess the best sensory qualities for oil production. Therefore, harvesting time is frequently a compromise between harvesting efficiency and final oil quality.

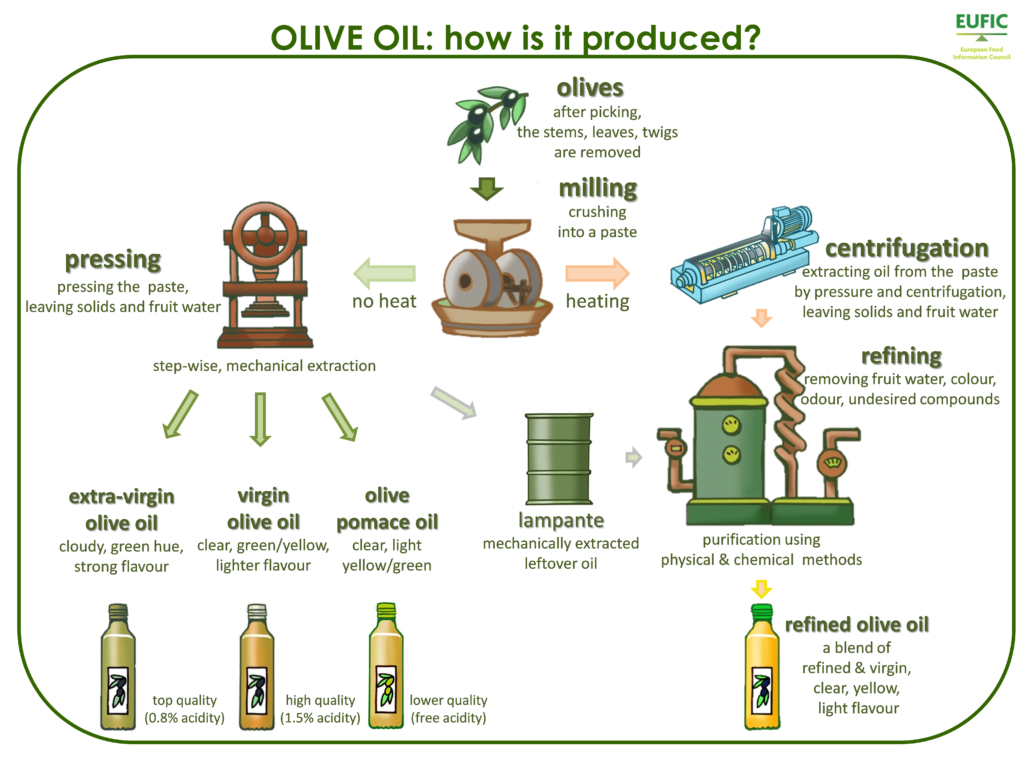

After harvesting, the olives are washed to remove dirt, leaves, and twigs. After the twigs are filtered out with grids, the fruit is ready for processing into oil. Fewer than 24 hours from harvest to processing produces the highest-grade oils.

Modern olive mills are partially or fully automated and have replaced granite crushers with metal crushers. They consist of a stainless steel body and a stainless steel crusher that rotates at high speed. The olives are typically thrown against a hammer-shaped metal grating, thus the name hammermill. Alternatives include toothed disc, cylinder, and roller mills. Modern milling is very gentle in order to avoid overheating of the paste. Cold pressed (extra virgin) oils must not exceed 27˚C at any step in the processing of the oil.

Modern malaxers are horizontal troughs with spiral mixing blades. Typically, two or three cylindrical vats are used in tandem, mixing the paste at slow speeds (15–20 rpm) for anywhere between 20 minutes and 75 minutes. The vats are jacketed so that the paste can be heated or water added during this process to increase the yield, although that generally results in a lowering of oil quality. New malaxers have an atmosphere controlled by an inert gas (i.e., nitrogen or carbon dioxide) to reduce oxidation and produce higher-quality oils.

Following modern milling processes, the paste is pumped into an industrial decanter where the phases are separated using centrifugation. This step can involve a three-phase decanter or a two-phase decanter. Water can be added to facilitate the extraction process. The decanter is a large-capacity horizontal centrifuge rotating approximately 3,500 rpm. In three-phase decanting, inside the rotating conical drum is a coil that rotates more slowly than the drum. This pushes the solids out of one end of the system and the water and oil out the other end. Three-phase decanting results in loss of a portion of the oil polyphenolics due to the higher quantity of water used. It also produces larger quantities of vegetative water that then need to be processed and have negative environmental effects. Two-phase decanters were created to solve these problems. In this process, the olive paste is separated into two phases, oil and wet pomace. The decanter has two exits instead of three, and the water is expelled with the pomace, resulting in a wetter pomace. The two-phase decanter thus solves the phenol washing issue and uses less water, but increases the waste produced. Regardless of the process used for oil extraction, a final centrifugation process is needed to separate the oil from the vegetation water. Vertical centrifuges, operating at lower speeds of 6,000 rpm under controlled temperature conditions, are used for this purpose.

State-of-the art, continuous commercial olive mills can be purchased from companies like Gruppo Pieralisi. One of the company’s units is shown in the photo on this page. It is a closed system of continuous milling that provides minimal oxygen contact using a two-phase extraction process. This mill processes 3 tons of olives an hour.

The Sinolea method is yet another method to extract olive oil. In this process, rows of metal discs are dipped into the paste, and the oil preferentially sticks to the metal and is removed by scrapers in a continuous process. Based on the varying surface tension between the oil and vegetation water, the oil adheres to the steel plates while the other two phases remain behind. The Sinolea method continuously introduces hundreds of plates into the paste and is not very efficient, leaving lots of oil in the paste. The final paste still requires decanting.

Following processing, the oil is stored in large stainless steel tanks with nitrogen blanketing to protect it from oxygen. Although not necessary, virgin olive oil can be filtered prior to bottling. Diatomaceous earth is frequently used as a filter aid. Colored glass bottles are ideal packaging for olive oil because the colored glass blocks the UV light and is also impermeable to oxygen. Bottling under nitrogen is a recommended practice.